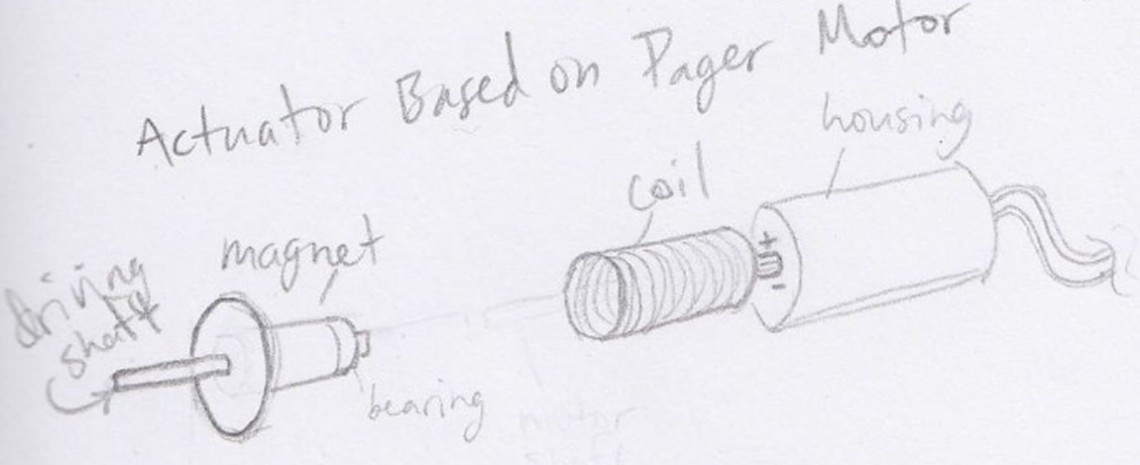

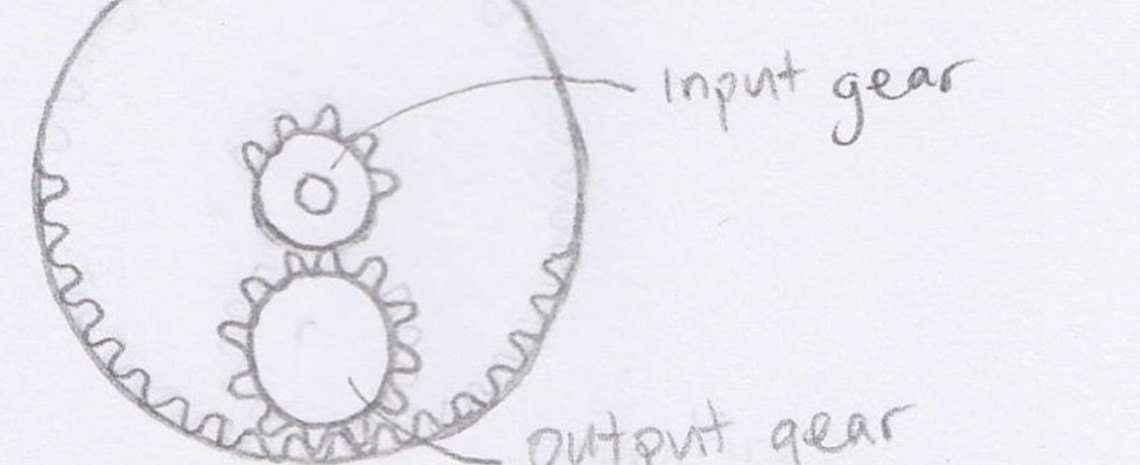

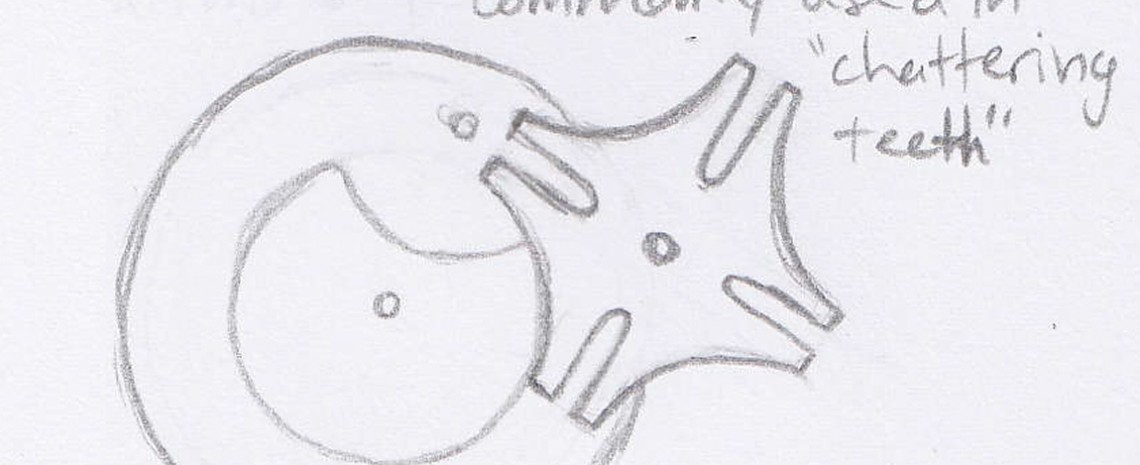

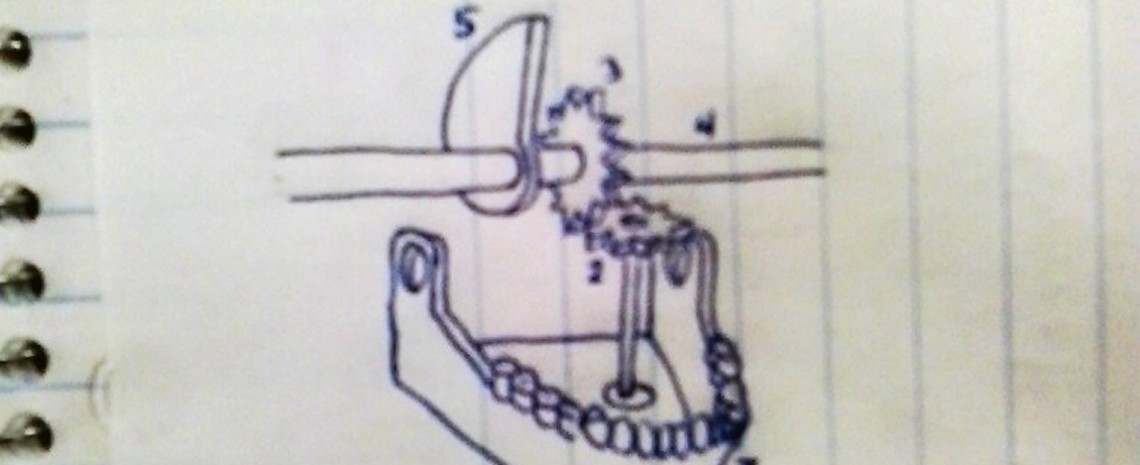

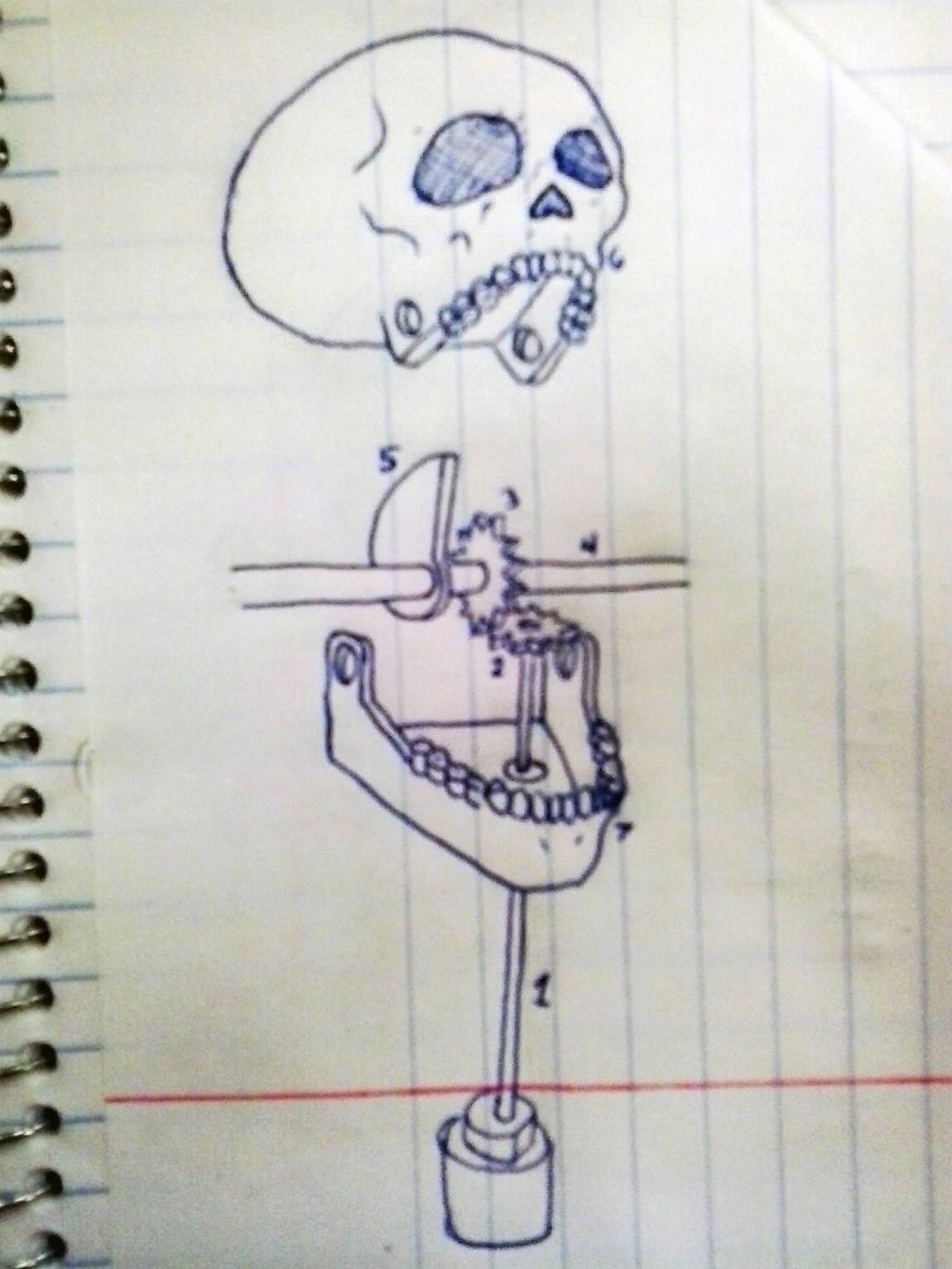

For the early wearables kit, the Maker Lab Team and I thought it would be interesting to recreate Trouvé’s skull stick-pin. The skull’s teeth gnash, and the eyes light up when it is turned on by a battery, which is placed in the wearer’s pocket. I’m currently designing the stick-pin using some 3D-modelling software. Then we’ll print both the skull and gear system using the Maker Lab’s Prusa i3.

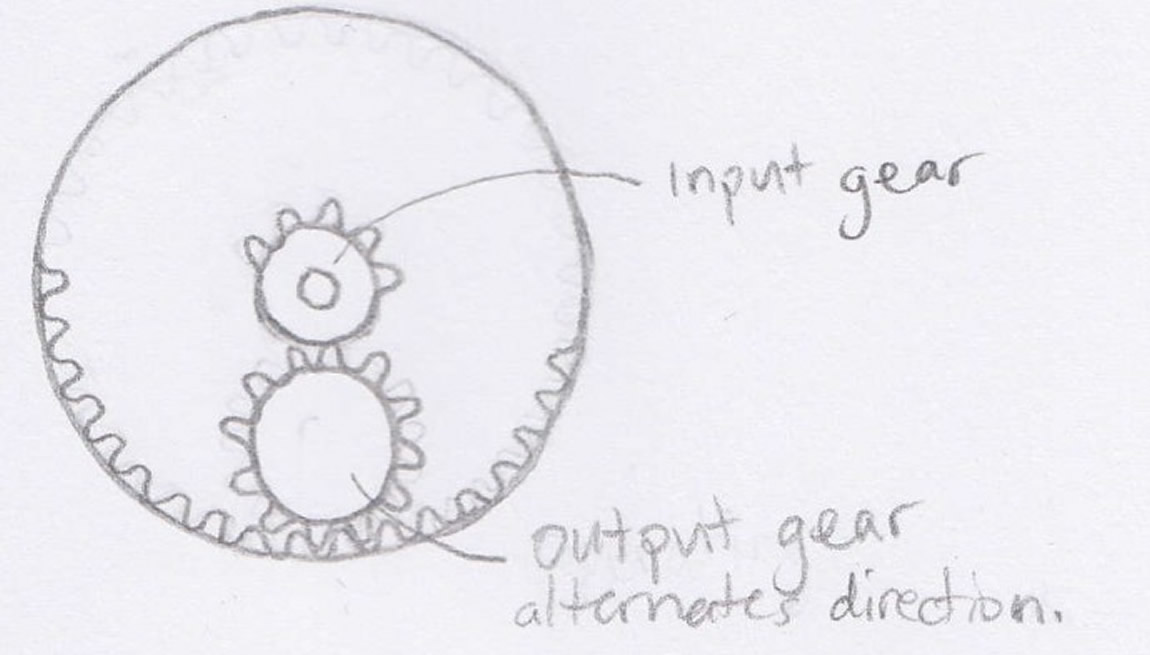

Trouvé apparently sought out a watchmaker to create the small operating mechanism that operates the jaw. This historical detail is interesting because watchmaking is a trade that has adapted to and been threatened by the battery (Trouvé’s own invention), not to mention digitization and, more recently, the demand for smart watches. Put differently, the makeup of Trouvé’s stick-pin is embedded in a long history of techniques used to express and understand time. Although neither the pin nor the project is really about watches or temporality during the Victorian period, the component parts we’re using correspond with keeping time during the late nineteenth century as well as skilled trades and analog manufacturing processes routinely subjected to obsolescence.

By redesigning Trouvé’s stick-pin, we are thus adhering to traditional gear systems while also maintaining a cultural perspective premised on the contingencies of interpretation. This approach is conducive to triangulating nineteenth-century objects and labour practices with their theoretical or socio-political coordinates.

To be sure, there’s a bit of irony here: the same technology that affords us a better understanding of objects and labour also risks mystifying manufacturing processes and their histories. 3D printing not only allows us to make more and sometimes better things; it also changes why and how we make them. That is, it changes the relationships we have with the very objects we create. If the production of an object is—in a WYSIWYG fashion—independent from many skills used to build it, then making things arguably becomes more about processing and production than, say, attaining manual skills or tactically solving problems.

In this way, a gain for academics, hobbyists, and makerspaces could be a loss for skilled trades and working classes. As such, throughout this project I have been considering this question: How can 3D printing be transformed by people who are antagonized by it? Alternatively, how can skilled trades and maker cultures encourage such transformations? In the spirit of art movements that have perverted their own mediums in response to emerging worldviews and technologies (e.g., the introduction of abstract painting alongside the development of photography), how can we foster cultures that resist the logic of obsolescence and instead favour hybrid practices?

Post by Katie McQueston, in the KitsForCulture category, with the fabrication tag. Images for this post care of Katie McQueston.

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Research Assistant Positions: 2015-16()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » MLab at the SAA Annual Meeting()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Designing Guides for Early Wearable Kits()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Mécanisme à l’intérieur de la tête de mort()