In the guide for our early wearable kit (which is part of the Kits for Cultural History series), we wanted to include historical information about Gustave Trouvé’s electro-mobile jewellery, the contexts in which the jewellery was worn (or not), as well as suggestions for building one of the pieces (a skull stick-pin) in multiple ways with numerous mechanisms. This approach assumes technologies are similar to texts: as objects, they are subject to interpretation, and they undergo revision prior to dissemination. Since early wearables were produced between the 1850s and 1880s, we began our design process by researching grangerizing techniques popular during the Victorian period. Grangerizing involves annotating an existing work with images and text. As Amanda Visconti suggests in her entry for the ArchBook project, grangerizing is comparable to common-placing and scrapbooking and nearly synonymous with extra-illustrating. She adds: “Because of changes in printing, the rise of scrapbooking, and changes in class differences, [g]rangerizing drifted away from a form of displaying wealth to a technique of hacking the book.” (For more on hacking the book, see Visconti’s “Shuffle, Fragment, Sort, Hack this Bibliography.”)

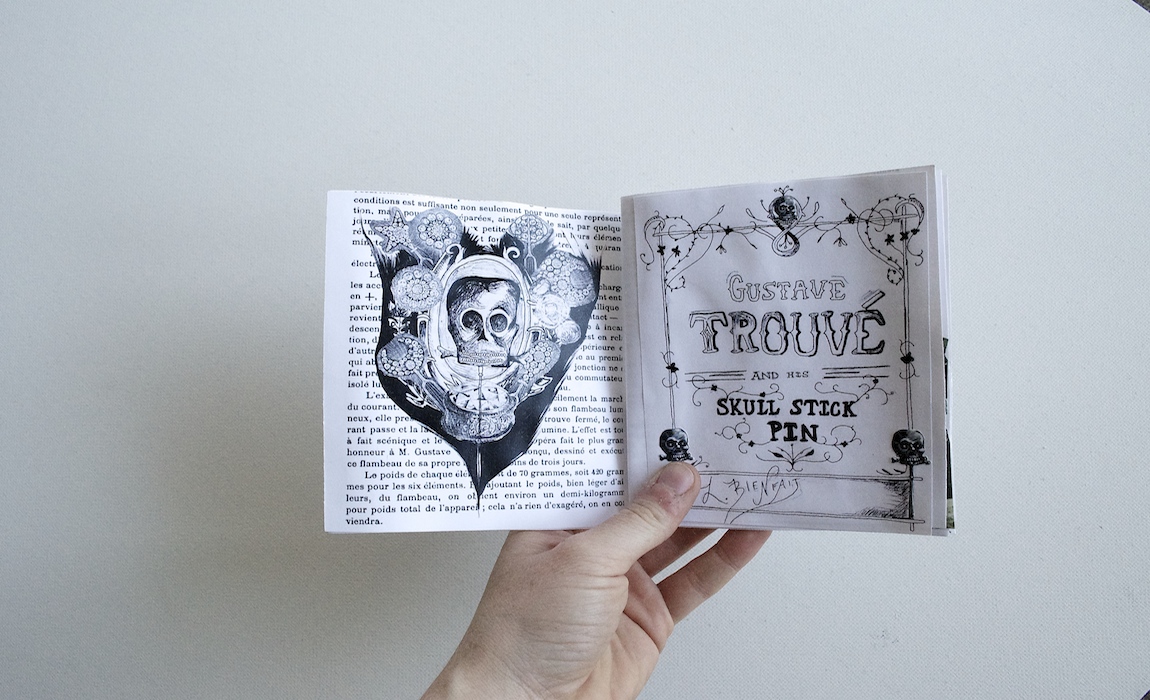

Inspired by grangerizing as well as Visconti’s notion of book hacking, we used Georges Barral’s biography of Trouvé, Histoire d’un Inventeur, as the base text for our early wearable guide. Since we could not work from a hardcopy of the biography, we instead printed a public domain PDF. We then used Victorian illustration styles to create something between a grangerized book and a zine. Zines usually represent subcultures or ideas that are not generally acknowledged in popular publications. Thus it seemed fitting to use the zine format to represent an inventor who, despite his numerous inventions and contributions to Victorian culture, remains minimally referenced in scholarly work. Some of our design influences include riot grrl weekly zines, various punk zines from the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, and Anna Anthropy’s videogame work, all of which combine forms of cultural criticism with experimental media.

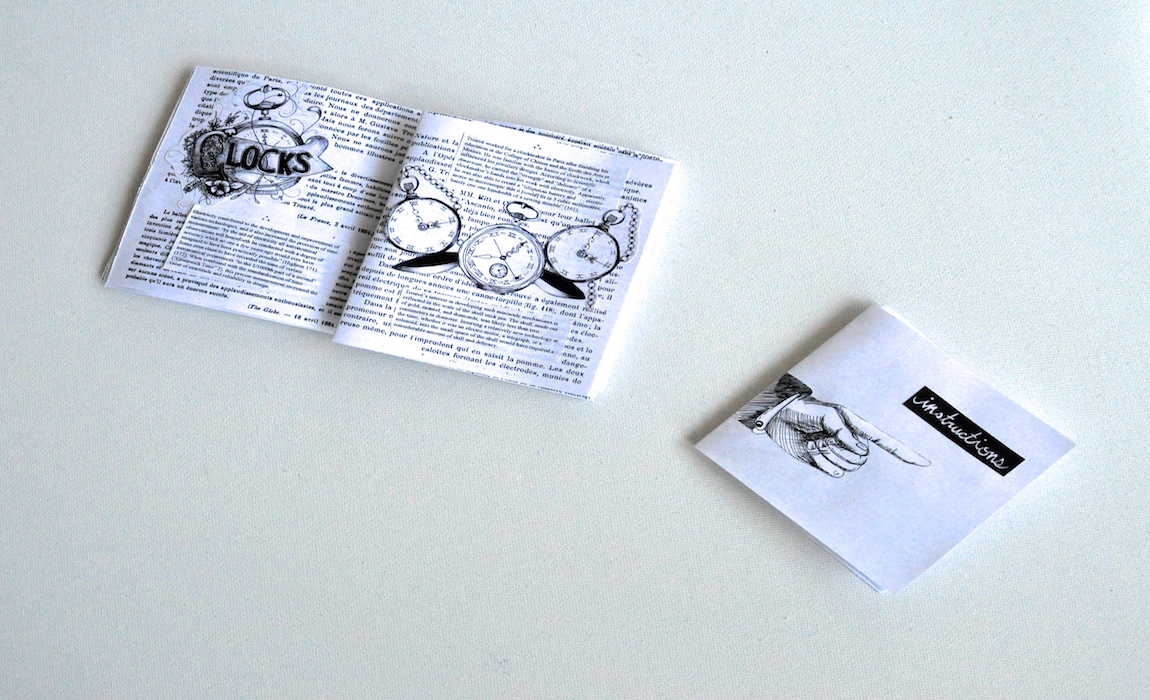

During the process of making the guide, we designed three rough prototypes: the first could be read like a regular zine but also unfolded into a map-like series of instructions for building early wearables, the second intertwined instruction and information in a vertical format, and our final design contained a removable mini-booklet of instructions inserted into the grangerized text. By using manual and digital methods to mix contemporary and Victorian aesthetics, we wanted these physical guides to look and feel collaged. We also wanted them to exist as middle states, somewhere between distinct moments in history.

Early in 2015, we made mock-ups of how we thought we might integrate historical newspaper clippings, annotations, illustrations, and Barral’s biography through collage and drawings. Here’s one instance of those mock-ups:

As the guide progressed, we developed the collaged aesthetic:

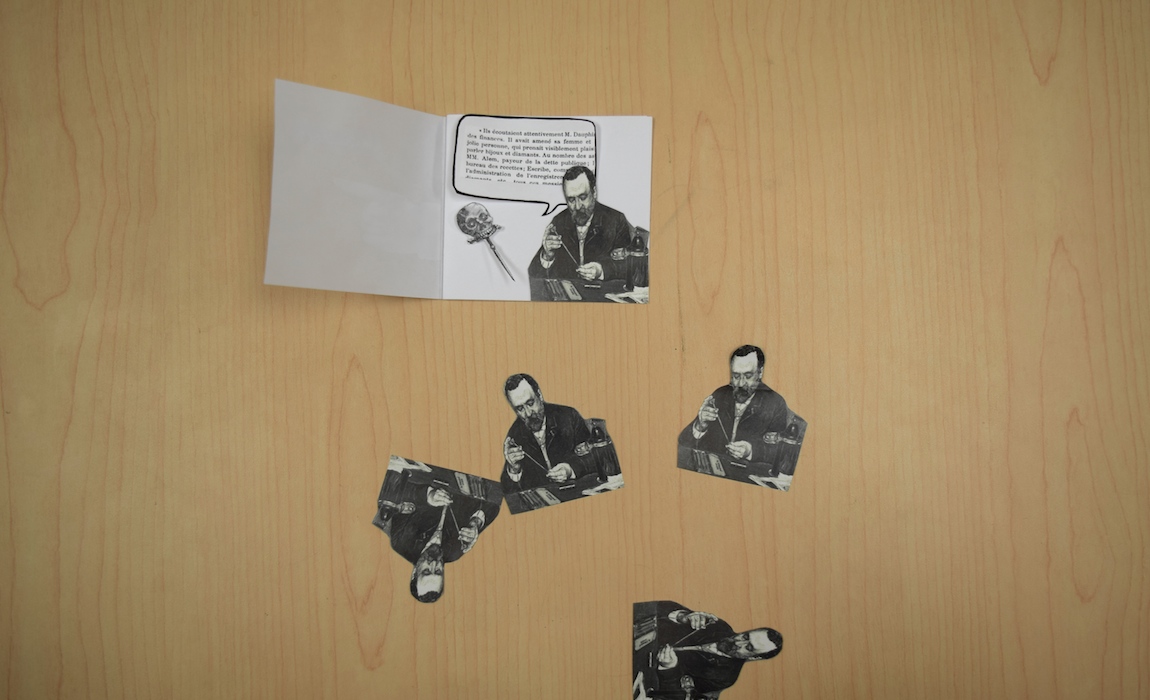

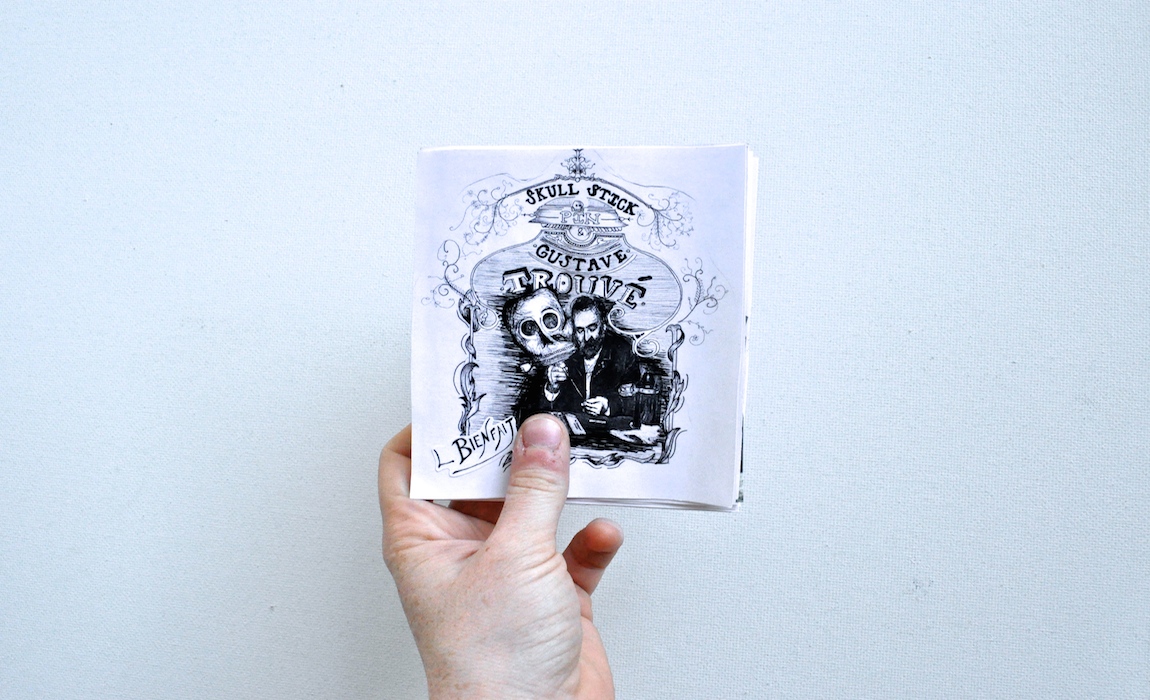

For the inserted instruction booklet, we modified a photograph of Trouvé and turned him into a narrator, who playfully conveys instructions for building the stick-pin in multiple ways. Should audiences trust their narrator? Is he reliable? What is his bias? His pedagogy?

Since we are foregrounding the role that prototyping, revision, and decision-making play in the construction of technologies, we wanted Trouvé’s narration to give the sense that the reader/builder is meant to explore tangible possibilities alongside him instead of somehow replicating his procedures, which—to be clear—we cannot fully recover or even mimic in 2015. The instruction booklet can be read in context with the rest of the guide, but it can also be removed and used during the assembly process. Because the instructions can be held in hand, audiences don’t need to stare at a screen while they are unpacking a kit or making a wearable.

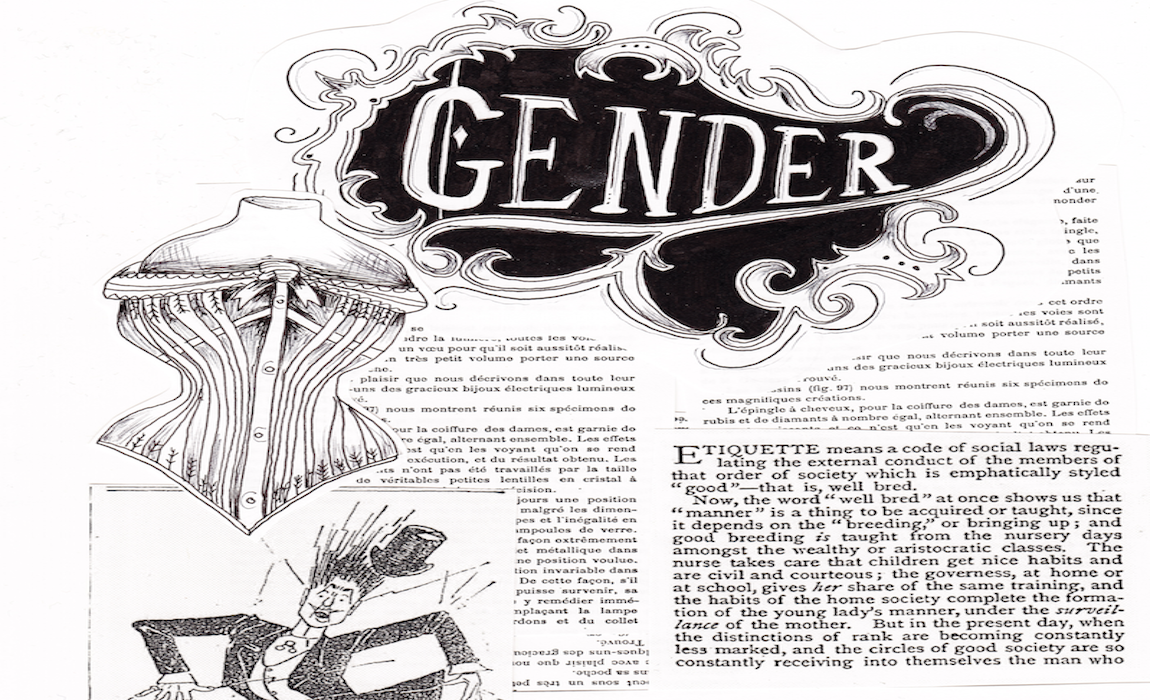

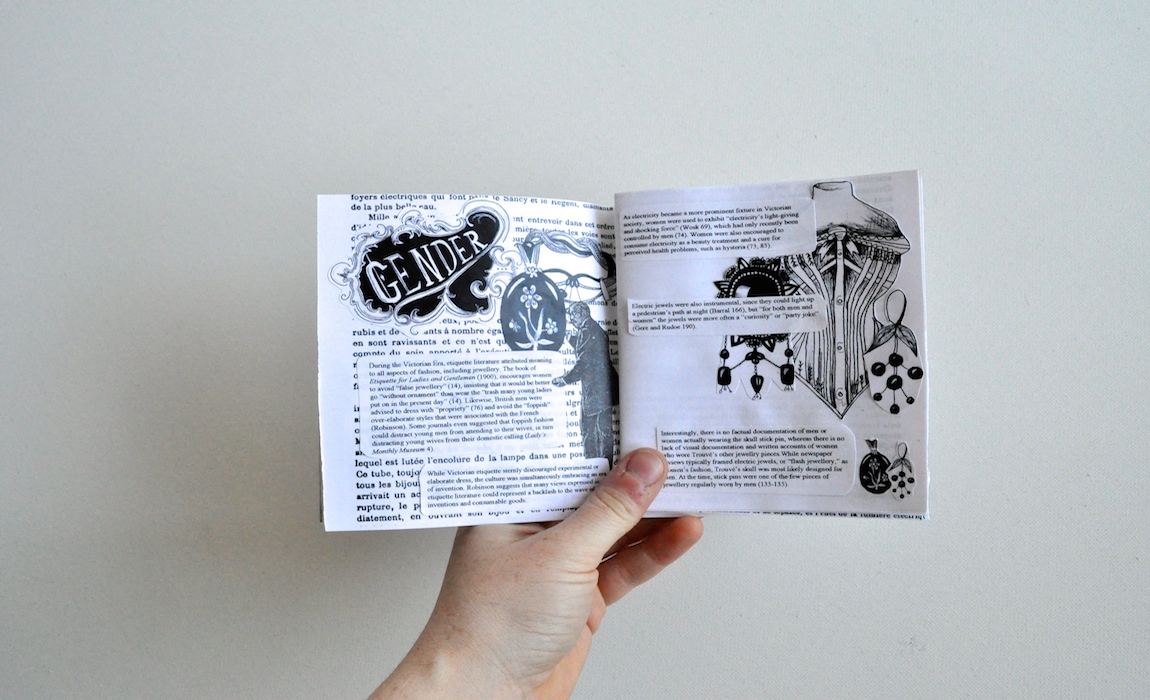

In order to situate early wearables in the context of Victorian culture, we explored six aspects or “keywords” (in the tradition of Raymond Williams’s work) that may have contributed either to the skull’s design or to the way early wearables such as the skull stick-pin were received. The sections on clocks and telegraphs briefly touch on the way those technologies may have influenced Trouvé’s design choices, while the segments on class and gender give some context for cultural etiquette around jewellery during the period. The mourning section addresses mourning jewellery traditions in Victorian culture, where skulls were significant symbols central to what Susan Elizabeth Ryan calls “dress acts.” Additionally, the section about performance describes instances where Trouvé’s jewellery was worn publicly. As often as possible, we drew this information from books and newspaper articles from the period. Below is a photo of the gender section. In the future, we’ll be adding more sections, including sections on the role race, positivism, and electromagnetic worldviews played in early wearables.

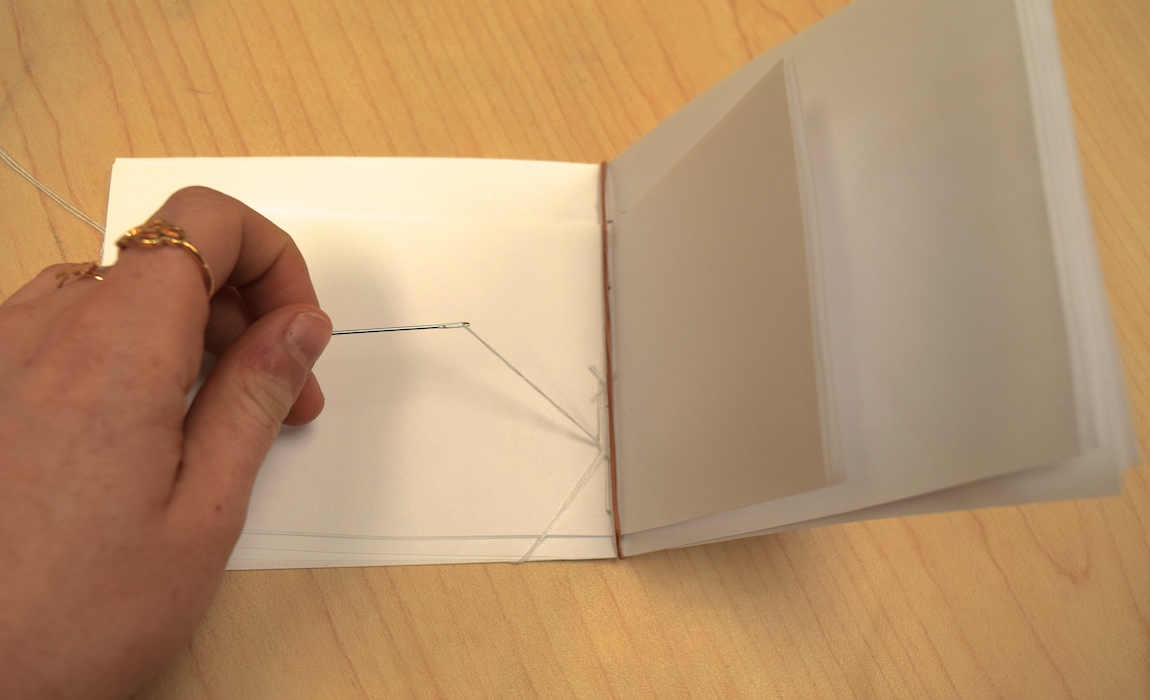

To bind the guide, we used a pamphlet stitch and nested the instruction booklet inside the guide with leather string:

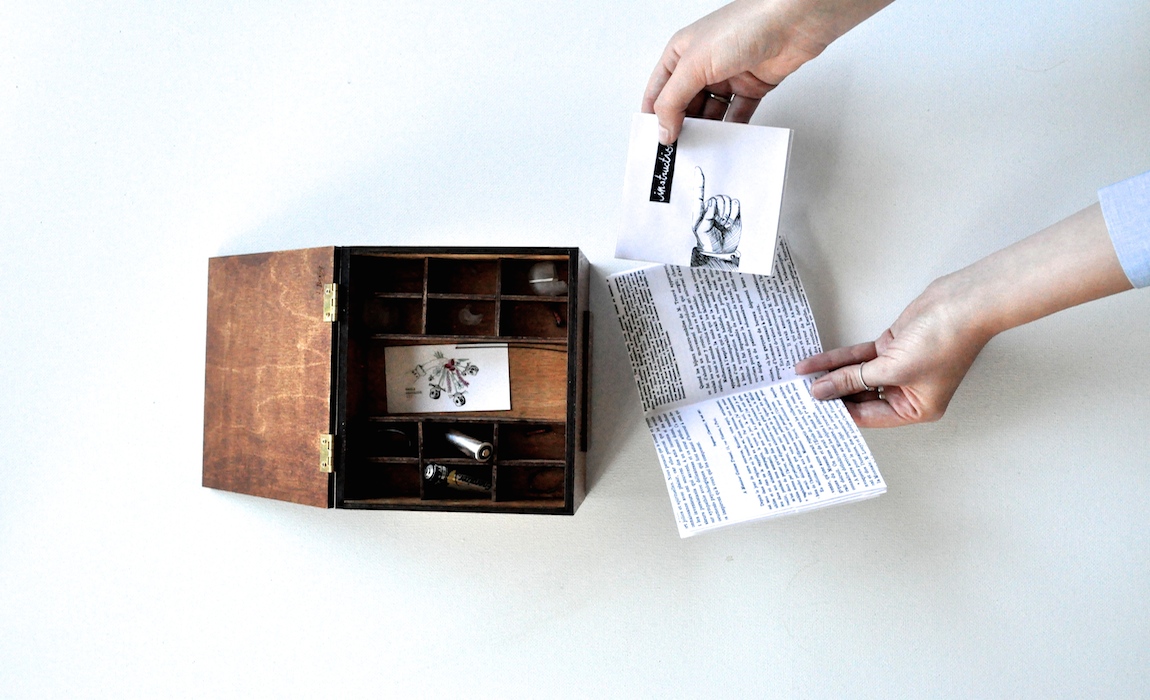

Finally, the guide was ready to be placed inside the kit:

Together with a calling card, of course:

Post by Danielle Morgan, attached to the KitsForCulture project, with the fabrication and versioning tags. Images for this post care of Danielle Morgan and the Maker Lab. Thanks again to Amanda Visconti for her history of grangerizing: https://drc.usask.ca/projects/archbook/grangerizing.php.