While working on the design for both our “Tennis for Two” and “Early Wearables” kits, several of us in the lab have been considering how the material composition of a kit can (or should) communicate information. With that issue in mind, I’ve decided to take a sort of “medium is the massage” approach to designing our kits. For instance, a traditional cardboard box with printed graphics speaks to the conventions of consumerism. And although speaking through this model can be rich cultural territory, I want to make sure I seriously consider how the box could participate in the processes of teaching and learning via tacit, critical engagement. Therefore, instead of decorating a box to openly advertise its contents, we have chosen to play with a casing’s seemingly inherent, dynamic ability to at once announce and conceal, all in order to better acquaint the participant—hands on—with the cultural contexts that are so critical to the material histories of technologies. This way, the packaging or casing of a given kit can be seen not only as a decorative or protective cover, but also as a kind of informative interface.

Early Wearables

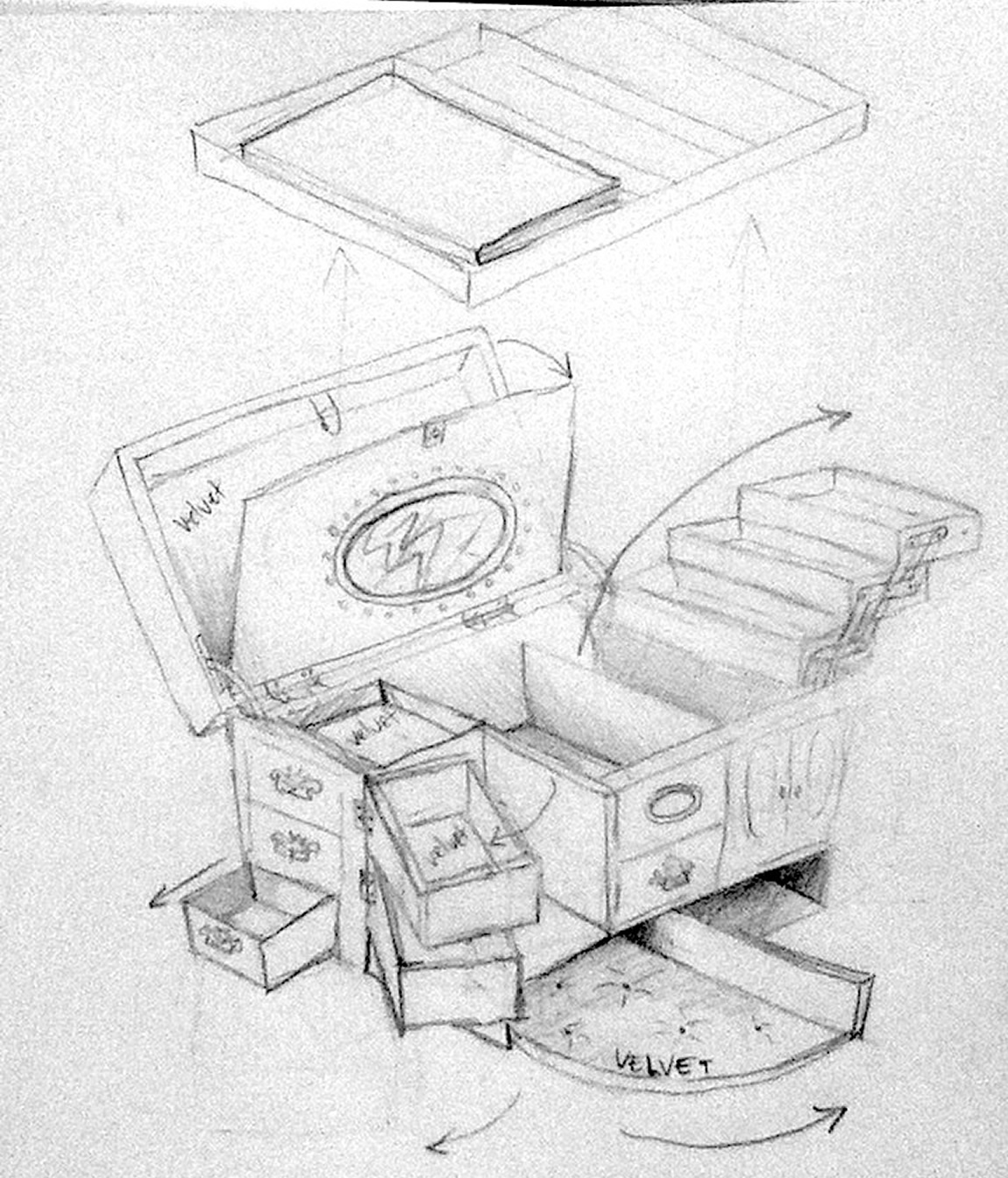

Trouvé’s nineteenth-century wearables are influential because of their scientific achievements as well as how they welded technological innovation to social life, everyday practice, and people’s bodies through the use of jewelry and other accessories. Inspired by Nina’s research, in the lab Zaqir, Shaun, and I found it extremely important to express the intimacy of early wearables with and through our kit. So I decided to build a handmade period jewelry box (see sketch above), which is similar to what wearers of Trouvé’s pieces might have had in their bedrooms. Through the work of contextualizing these pieces as jewelry, I also asked myself if there were other early instances of wearable electronics that were not marketed as fashion accessories (e.g., mining hats and other electronics worn on bodies for industrial use). This comparative approach no doubt enriched the design process, not to mention our understanding of material history.

Tennis for Two

The materials for this kit design were also motivated by packaging’s historical contexts. Tennis for Two was an early DIY game that relied in part on equipment and materials used for military applications. Alex, Shaun, Jon, and I found the narratives between gaming and military technologies to be provocative subjects—topics we want to unfold through the kit. For instance, placing the Tennis for Two components in a mid-twentieth-century ammo box (see example image above) is a way to reference these narratives without making the kit too muddled or ornate.

But will using evocative objects as cases for kits help us or our audiences better situate a kit within a specific historical context or critical paradigm? At this point, we’re not exactly sure. However, in this early stage of kits design, we are experimenting with evocative objects in order to invite the overlap of otherwise parallel histories (i.e., domestic, military, industrial, social, and cultural) through intimate engagements with materials. Is it possible that, by removing ourselves from more consumer-oriented design (e.g., the traditional cardboard box), we forfeit the ability to clearly speak to a participant’s desire to pick up and play with a kit? Or will these material juxtapositions—which communicate intuitively rather than didactically (much the same way that Dada and Surrealism used absurdity and dreamscapes as forms of protest against logical and insensitive scientific thought)—enable us to successfully engage audiences through tacit approaches to historical technocultures? On this front, more from us soon.

Post by Kaitlynn McQueston, attached to KitsForCulture, with the fabrication tag. Featured images on this post care of Kaitlynn McQueston and INCH Survival.