Proust’s modernism is the result of an experiment.

Nearly a quarter of a century after Proust’s passing in 1922, his niece opened a cabinet in her home to reveal stacks of notebooks and piles of torn draft pages that had been hidden away since the close of the nineteenth century. The mass of archival material, generated more than two decades before the appearance of Du Côté de Chez Swann, composed the manuscript pages of Proust’s nineteenth century novel—a novel Proust never finished.

The status of the manuscript materials that compose Proust’s unfinished early novel embody Proust’s non-linear sense of time. The narrative is fragmented across torn stacks of paper and seventy notebooks, some numbered and others left with no clear indication of their eventual location in the book. Throughout the pages, narrative contradiction and inconsistency are pervasive: the names of main characters often change suddenly and the same narrative episode can be found in multiple scenes, the details of which contradict each other. Proust constantly slips between third-person and first-person narration. The discontinuous shards of narrative that exist across these manuscript pages gesture toward a complete novel that will never exist, leaving Proust’s incomplete experiment at the edges of narrative fulfillment, in which the continuities of time, character, and narrative itself exist in a state of perpetual rupture.

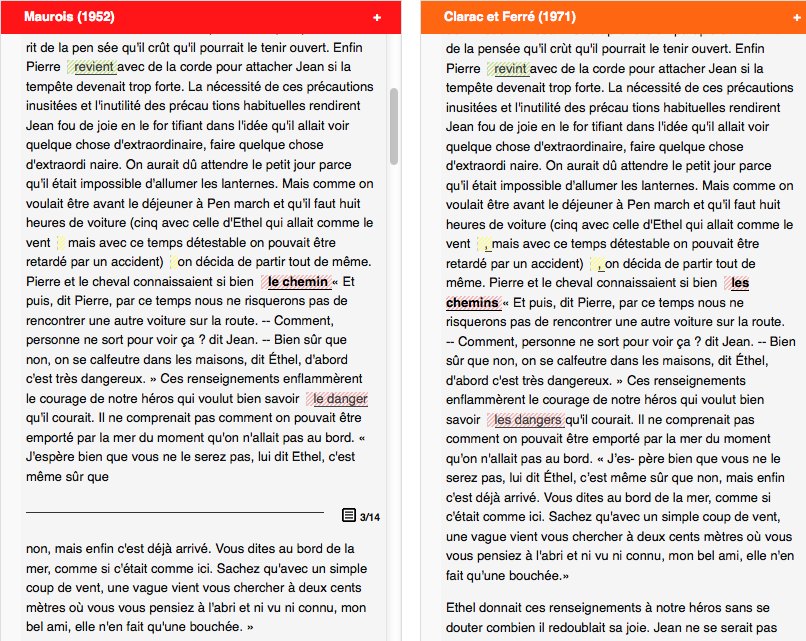

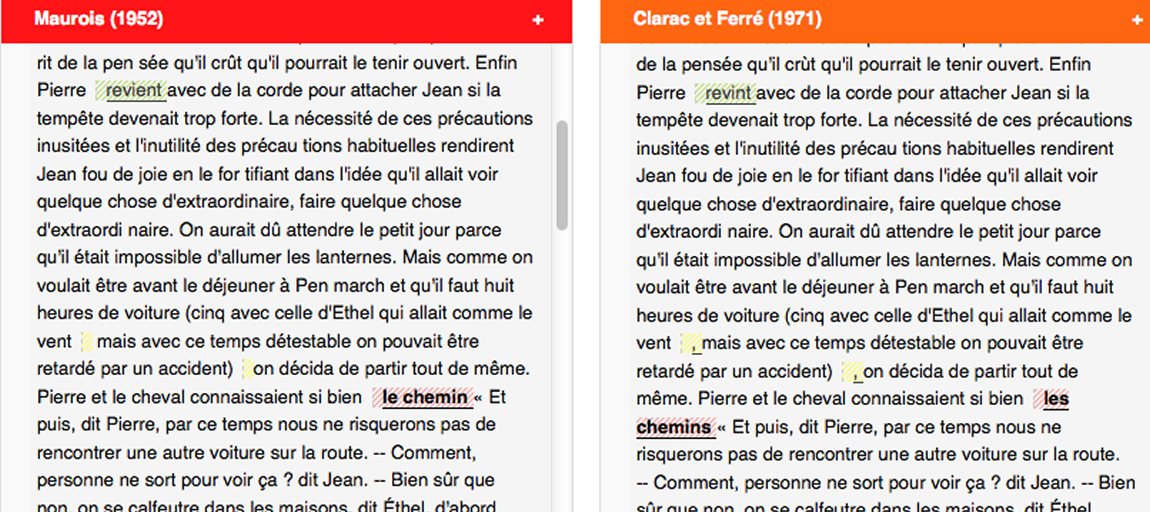

These are the materials that were handed from Mme. Gérard Mante-Proust to Bernard de Fallois, a doctoral student who, together with André Maurois, edited the first edition of Proust’s book, published in 1952. In order to bring Proust’s book to a state of editorial completion, Maurois and de Fallois stitched together the narrative ruptures that pervade in the original manuscript, silently correcting pronoun slips, editing and arranging contradictory fragments, and ordering the episodes such that they track the growth and maturation of Proust’s main protagonist. The published editions of Proust’s novel are named after the protagonist: Jean Santeuil.

The first edition of the novel, informed by editorial principles invested in finishing the composition that Proust abandoned in 1899, creates what is in many ways a nineteenth century novel. The first published edition of Jean Santeuil tracks the maturation of its protagonist from infancy to young adulthood. Rather than ending where it begins, or by deploying a telescoping first-person narrative to multiply the identities and epistemologies of its narrator/protagonist, this version of Proust’s early novel tracks the linear gestalt of Jean. In so doing, it elides the fractures and fissures that are essential to the formation of Proust’s modernist technique, deployed so masterfully in À La Recherche du Temps Perdu.

The task of faithfully representing the unfinished status of Proust’s manuscript was taken up by the editors of the second edition of the novel, Pierre Clarac and André Ferré, whose scholarly edition of Jean Santeuil first appeared in 1971. Rather than tracking the linear maturation of Jean, this edition represents the constant splitting and shifting of its protagonist, as Proust confuses him with his friend Henri, as the narrative frame in which his story is encapsulated constantly shifts and cracks, and as the events of his life are fragmented across contradictory versions of the same narrative episodes. Rather than concluding with the knowledge and experience of Jean’s early adulthood, this edition of the novel ends in pages of unsettled narrative fragments, disconnected shards of Jean’s life that shift between memories of his childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, memories which never resolve into a complete chronology.

The difference between the 1952 and 1971 editions of Jean Santeuil is more than the difference between two editorial principles. Each edition represents a different image of Proust’s early engagement with the techniques of modernism. The tension between rupture and continuity, between linear gestalt and between unresolved fragments of memory, situate Proust’s book at the edges of modernity. Reading the difference between the two editorial efforts to bring Proust’s modernist experiment to light offers an opportunity for working through Proust’s place as a modernist, as it engages with his concepts of temporal and individual development.

Versioning these two instantiations of Jean Santeuil represents Proust’s modernist experiment on the cusp of nineteenth century realism, as it negotiates between linear and fragmented notions of chronology, as it wrestles with the stability of its protagonist’s identity, and as it embodies the tension between continuous and shattered constructions of narrative. The project of versioning Jean Santeuil does not simply invite the reader to view the genesis of Proust’s modernist technique, but to actively work through the genesis of that technique as it is reconstructed through an electronic interface. The process of reading and representing Proust’s modernist experiment online therefore reactivates the editorial process of constructing Proust’s modernism, inviting the reader to participate. More details on how the computational processes used to version Proust activate Proust’s complicated understanding of temporality will follow in my next post.

Post by Alex Christie, attached to the ModVers project, with the versioning tag. Featured images for this post care of Alex Christie and his use of the MVP’s modVers tool.

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Hands-On Textuality()

Pingback: Proust at the Edges of Modernity | Modernist Versions Project()