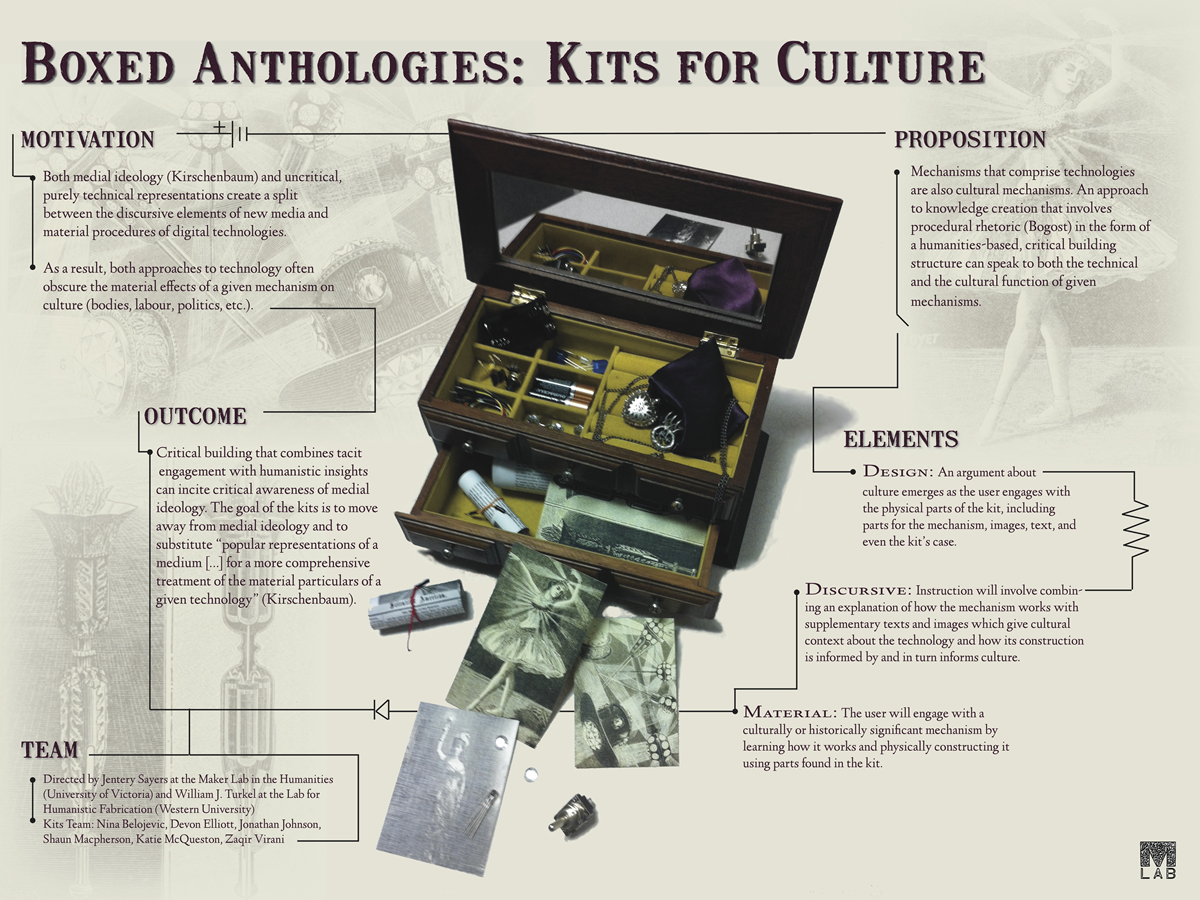

Last semester, Shaun Macpherson and I had the opportunity to attend the annual Western Humanities Alliance (WHA) meeting at the University of California, San Diego. The topic of the two-day event was “New Modes of Scholarly Communication,” with a keynote talk delivered by Kathleen Fitzpatrick (of the MLA). Alongside the many innovative, insightful, and inspirational presentations that we had the pleasure to see, Shaun and I presented a poster on the lab’s “Kits for Cultural History” project. As I argue elsewhere, we consider the hands-on engagement inherent to the kits an important way to make scholarly arguments away from the screen and off the page. Rather than only describing technologies and media, the kits encourage scholarly engagement through the reconstruction of historical devices. To borrow a term from Ian Bogost, arguments are made through “procedural rhetoric” that moves the audience’s attention beyond digital spaces. A complex combination of cultural and technical processes anchored in a historical mechanism is broken down into smaller components, which collectively make an argument and encourage a self-reflexive stance toward media history. Put this way, a key aspect of the kits project is the stimulation of a literacy that resists what Matthew Kirschenbaum calls “medial ideology” (i.e., the substitution of the material particulars of a given technology for popular representations of media).

Nina Belojevic and Shaun Macpherson Presenting Kits for Cultural History at UC San Diego (Photo by Sarah McCullough)

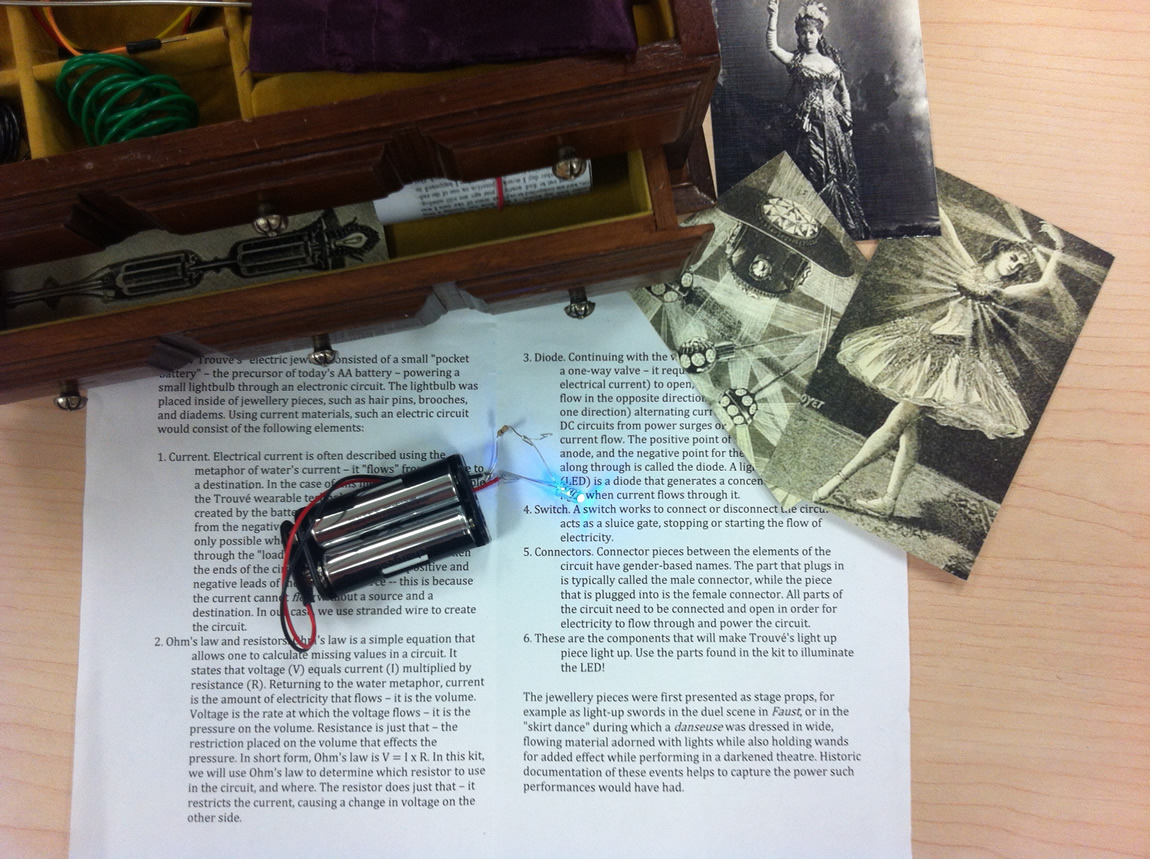

In order to communicate how the kits practically achieve our goals, we presented an early prototype at the WHA meeting. In the spirit of the kits series, we used a physical demonstration to convey how the project works and invites interpretation. The particular kit we used focuses on electric jewellery created by the nineteenth-century French engineer, Gustave Trouvé. In the 1870s and 1880s, Trouvé created illuminated brooches, diadems, and hat pins that were powered by two- to four-volt batteries. Although these pieces were initially designed for stage use, they quickly became fashionable in certain circles of Europe. Through this kit, we are using Trouvé’s work to unravel and historicize the very notion of “wearables” or “wearable technologies,” which are often associated with more contemporary research by “cyborg” practitioners such as Steven Mann.

For now, then, we are calling this kit our “early wearables” kit. It contains the parts required to construct a simple, battery-powered circuit that uses a small LED to illuminate a filigree hairpin. We also included supplementary materials, including pictures of women modelling Trouvé’s pieces, a handbill for a production of Faust (for which Trouvé created light-up swords), and instructional materials that explain the basic principles of circuitry. The instructional materials describe the functions and cultural significance of the parts in the kit, encouraging audiences to explore the historical contexts and discursive elements of early wearables.

Prototype of the Early Wearables Kit at UC San Diego (Photo care of Nina Belojevic and Shaun Macpherson)

As Shaun explains in “Publish This Kit (Part II),” the instructional materials work in a manner that encourages audiences to assemble the circuit while situating the mechanism in material history. In this kit, a description of electrical current also explains how the “hard” and “soft” distinctions between electricity and the materials that conduct it are informed by late nineteenth-century gender politics. The construction of the circuit makes note of “male” and “female” connector pieces and other gendered terminology, and the design of the jewelry piece itself speaks to how the original devices were engineered to be modelled on women’s bodies, rendering them display-objects for male innovation (a tradition that is ultimately bound up in the production of wearables). Rather than simply following instructions, audiences are thus prompted to gain a deeper understanding of wearable technologies and their contexts. In other words, the kits employ what might be understood as a humanities approach to technological literacy: they promote an attention to technical particulars while fostering self-reflexive building and a cultural awareness of mechanisms.

During the poster session at the WHA meeting, we had the wonderful opportunity to speak in person to a large number of attendees, who directly engaged our prototype; they picked it up, touched the component parts, and asked questions about the ways in which the elements would work together. These interactions gave us the opportunity to gauge the kind of scholarship the kits prompt. Once the participants were able to see, touch, and experience the kit, they also contributed insightful comments and questions for us to consider as we further develop the project: What is the scholarly apparatus of the kits? How will they be disseminated? How will they be used? How (if at all) will they intersect with other modes of scholarly communication, including journal articles and monographs?

Prototype of the Early Wearables Kit at UC San Diego (Photo care of Nina Belojevic and Shaun Macpherson)

As we continue to work on the kits, we will keep in mind the ways they can function as a form of scholarly argumentation. The kits attempt to circumvent the critical risks associated with technological determinism by integrating actual objects and material processes into scholarly communication. For example, in a field like comparative media studies, one could imagine a journal article that walks audiences through the assembly of a kit and, in doing so, digs into the material particulars of a historical mechanism. Such an article would demand attention to the page or screen as well as the physical content of a kit. Since we also consider the kits relevant to settings beyond academic campuses (e.g., public museums and other memory institutions), the procedures at work in them enact arguments distinct from what’s achievable via the screen or page alone.

Post by Nina Belojevic in the KitsForCulture category, with the news, physcomp, and fabrication tags. Photographs in this post care of Nina Belojevic, Shaun Macpherson, and Sarah McCullough. The “Boxed Anthologies” poster (top of page) was made by the Maker Lab Research Team, influenced by Fluxus.

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Cultural or Technological Determinism?()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Building Trouvé’s Skull Stick-Pin()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » MLab at IdeaFest: “Book Nerds in a Lab”()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » The Kits for Cultural History at HASTAC 2014()

Pingback: Yes We Can. But Should We? (Cultural Heritage Edition) | Brandon Locke()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Designing a Case for a Kit()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Kits for Cultural History()

Pingback: What I’m reading 16 Jul 2015 through 22 Jul 2015 | Morgan's Log()

Pingback: Maker Lab in the Humanities » University of Victoria » Bijoux Mécaniques()